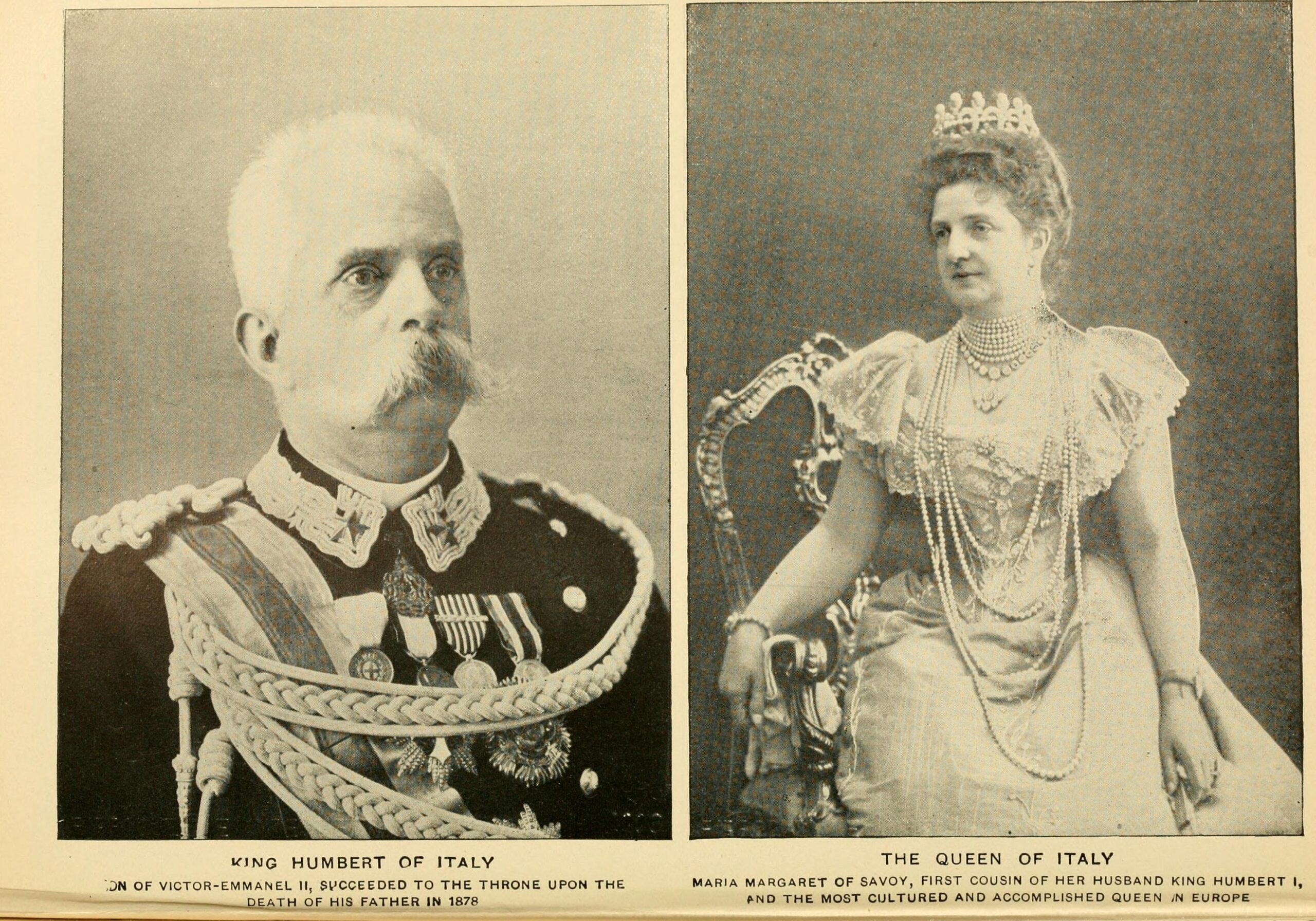

Back in 1889, Queen Margherita of Italy was visiting Naples with her husband, King Umberto I, when she fell ill. Unable to leave her royal residence, she requested that dinner be delivered to her door by the famous chef Raffaele Esposito. Rising to the occasion, Esposito designed a pizza to represent the colours of the Italian flag, topped with tomato, mozzarella, and fresh basil.

The pizza was so good, and the review even better (they still mattered back then), that the chef named his mozzarella and basil creation after her. And so the Margherita pizza was born.

As was the delivery format.

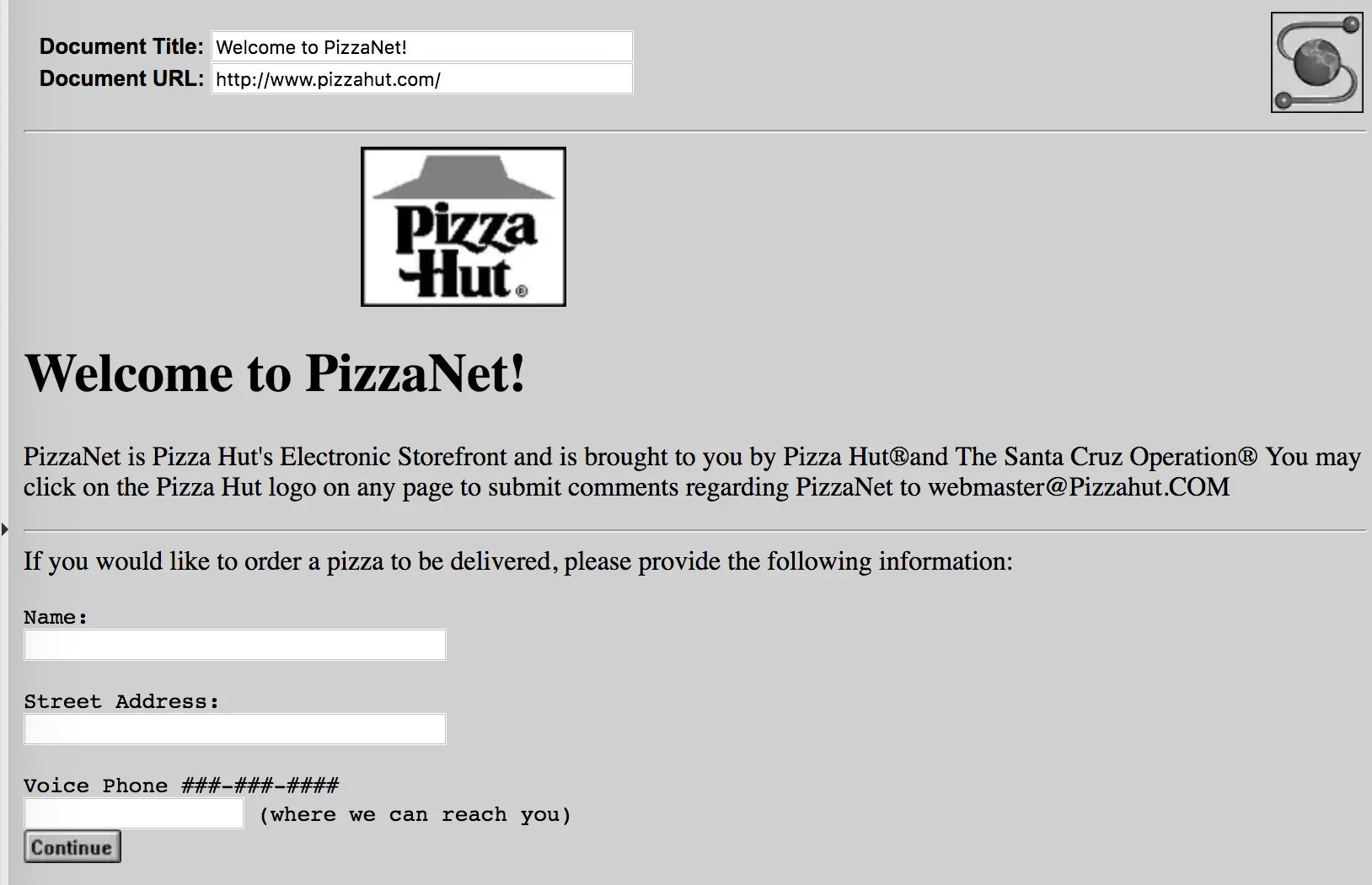

Fast forward 100 years or so, and the first thing ever sold on the internet (or World Wide Web as we used to call it) was, fittingly, a pizza. Ordered through PizzaNet, a website created by Pizza Hut for customers in the Santa Cruz area of California, the order was submitted via a basic online form, transmitted to a centralised Pizza Hut server in Wichita, and then relayed back to the Santa Cruz branch through a freshly installed internet connection.

Today, ordering food to your door couldn’t be easier. It is fast and frictionless, the food is warm (usually), and the options are endless.. But this convenience has come at a cost. Beneath the modern food delivery boom, things are starting to sour.

In just a few decades, the humble takeaway has transformed from an occasional Friday night indulgence into an everyday fixture of modern life. This shift hasn’t come without consequences. The rapid rise of food delivery has introduced complex new challenges, including the precarious working conditions faced by gig economy couriers, growing concerns over road safety in urban centres, and an increasingly uneasy dynamic between powerful tech platforms and the communities they serve.

A tradition that began as a royal indulgence and later became an internet novelty has now grown into a £3.8 billion industry in the UK, with the average consumer spending around £820 per year on takeaways. But increasingly, the person delivering your pad thai may never have set foot in a traditional restaurant, at least not in the way we used to understand one.

Behind the scenes, a delivery-first ecosystem is reshaping the food industry. It is driven by dark (or “ghost”) kitchens, delivery-only facilities often built by the tech platforms themselves, designed purely for speed and scale. They’re marketed as a way for big food brands to ‘test’ an area before opening a physical site. But their growth comes at a cost.

Dark kitchens siphon demand away from high street restaurants and reduce the incentive to invest in bricks-and-mortar venues. In some cases, they bring real disruption. A site in Camden, for instance, was found to have over 1,800 alleged breaches of planning conditions in 2022. Another, in Archbishop’s Park, Lambeth, drew repeated complaints of antisocial behaviour from drivers and even reports of raw meat dumped in the street.

At the other end of the transaction are the delivery drivers. Often paid per delivery and classified as “self-employed”, riders are at the mercy of big tech’s algorithms. In July 2025, drivers in Hartlepool staged a three-day strike over pay, with some claiming they earn as little as £6 an hour. Meanwhile, European app Glovo sparked outrage by offering a ‘heatwave bonus’, giving drivers a few extra cents per delivery during the hottest part of the summer, only to quietly scrap the scheme following a public backlash over its questionable morality.

These pressures are pushing riders to dangerous extremes. In a bid to increase their earnings, some are modifying e-bikes to exceed speeds of 30mph, sometimes with tragic consequences. At the same time, reports are emerging of legitimate delivery accounts being sub-let to undocumented or ineligible workers, a practice that not only exposes vulnerable people to exploitation but also erodes accountability when things inevitably go wrong.

Taken together, these issues point to a wider pattern, and one not limited to food delivery. From Uber’s early disregard for taxi regulations to the chaos caused by dockless Lime bikes and e-scooters (we could write a whole article on that alone, but we’ll just leave you with “Lime bike leg”), tech disruptors have prioritised growth over the real-world consequences of their operations, whether that be overworked riders, unsafe roads or a declining high street.

The ‘convenience economy’ isn’t going anywhere, and nor should it. But as tech platforms reshape the fabric of urban life, it’s no longer enough to dismiss the harm they cause as side effects or unintended consequences. Companies like Deliveroo and Uber Eats are part of the furniture now That means accepting responsibility not just for their end-users, but for the cities and communities they operate in. A frictionless future shouldn’t come at the cost of those who help hold it together.