“We’d have chippy supper four, five times a week,” Gary Neville (once footballer, now fish and chip thought leader) once said. There was a time when a fish supper wasn’t a monthly indulgence, didn’t break the bank, and didn’t have to compete with the dizzying variety of food Britain now takes for granted. It was a food staple, woven into the weekly rhythm of British life.

So how did fish and chips become so popular? The answer explains both its rise and its fall.

Long before it became a seaside mainstay, the dish rose alongside industrialisation. The marriage of new railways and trawler fishing ensured factory workers, many of whom didn’t have kitchens of their own, were fed. By the early 20th century, there were tens of thousands of chippies across Britain, peaking at around 35,000 in 1927. So central had fish and chips become to the national spirit that they were famously never rationed during the Second World War.

But something changed. Today, there are closer to 10,500 fish and chip shops left in the UK and many are struggling. Cod prices have doubled in recent years. Energy bills have soared. Trade bodies have warned of a potential “extinction event” for the industry.

The economics are brutal: there’s a limit to how much punters will stomach for battered cod, and raising prices means losing customers. Increasingly, chippies are padding their menus with burgers, pizzas and, you’ve guessed it, chicken, just to survive.

At the same time, Britain’s tastes have widened. Younger generations have grown up surrounded by far more choice, and fish and chips no longer sit at the centre of everyday meal plans the way they once did. Immigration reshaped the national menu too, both by bringing entrepreneurs who opened different types of takeaways, and by creating demand for cuisines where fried fish never featured.

More recently, delivery apps multiplied choice overnight. Fish and chips, once cheap and ubiquitous, became fragile: expensive to produce, difficult to transport, and ill-suited to an increasingly online-first way of eating.

Chicken, meanwhile, did the opposite. Whether roasted, grilled or, of course, fried, it benefited from industrial farming, global supply chains and decades of American fast-food influence. Cheap enough to anchor meals and familiar enough to appeal across cultures, fried chicken exists in many food traditions, from the American South to Korea, making it instantly recognisable and ready to travel.

That familiarity translated into scale. Chicken shops spread quickly across British high streets, stayed open later than pubs and chippies, and filled the gaps in the evening economy. KFC, once a novelty, embedded itself into British high streets and now plans to invest nearly £1.5bn in the UK and Ireland, opening hundreds of new outlets and creating thousands of jobs. The UK fried chicken market alone is estimated to be worth over £3bn, and it’s still cooking.

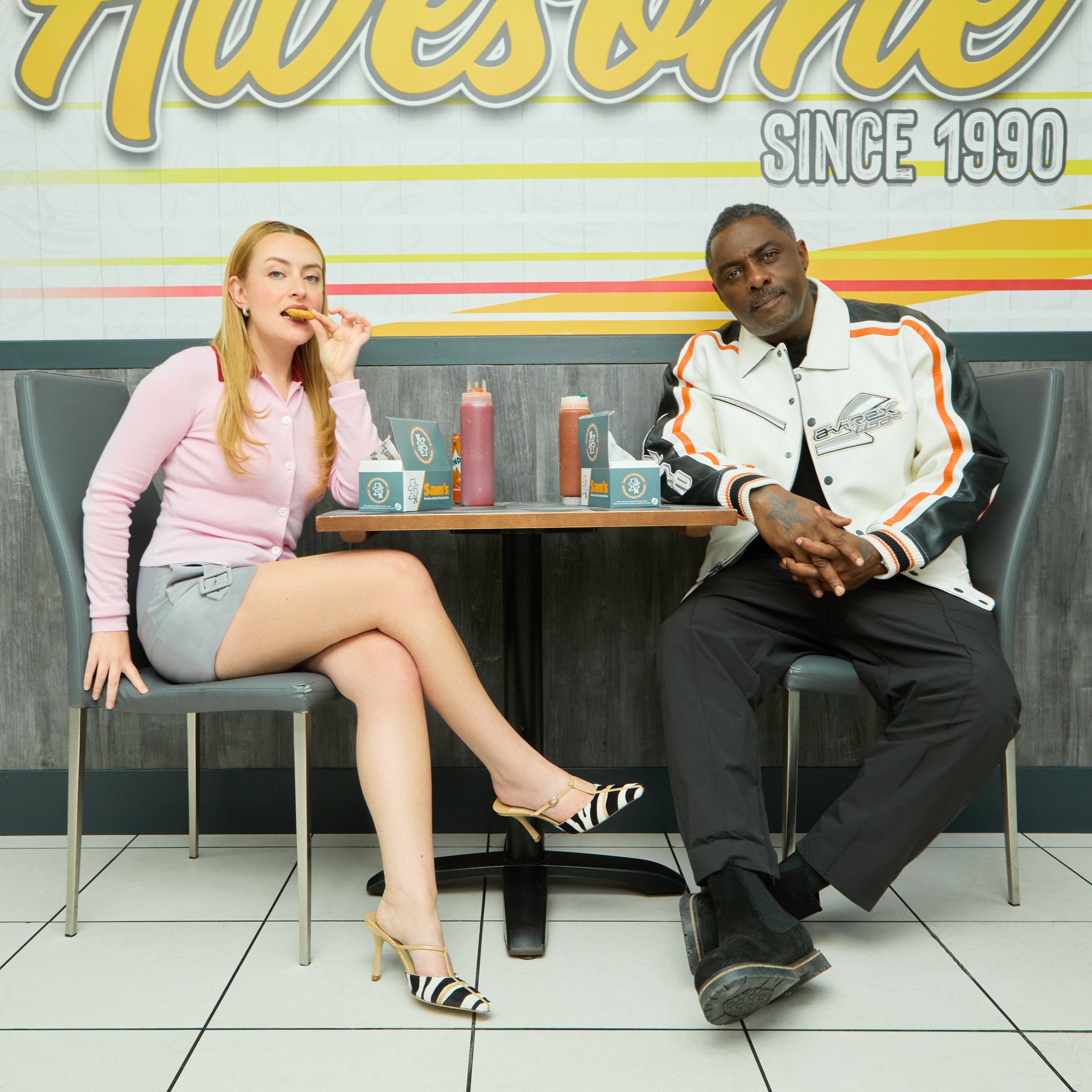

But chicken didn’t just win economically. It won culturally. Over the past decade, chicken shops have become more than just eateries. Amelia Dimoldenberg’s Chicken Shop Date, now more than ten years old, turned awkward interviews at sticky tables into must-do moments for global celebrities promoting albums, films and tours.

Before that, Elijah “The Chicken Connoisseur” Quashie’s Pengest Munch elevated London chicken shops from everyday post-school-fuel to cultural landmarks. And across the pond, Hot Ones proved the same point: chicken had become a global interview hook.

Fish and chips never quite made that leap. It remained rooted in ritual, memory and place, while chicken moved into pop culture, algorithms and the night time economy.

So where does this leave two cod, one portion of chips and a mushy peas?

Sustainability pressures, overfishing and rising costs make a return to mass affordability unlikely, at least for now. Fish may survive as something occasional, premium and largely regional.

Or it may re-emerge in new forms; anchovies and sardines gaining ground, tinned fish becoming Instagram-chic, or plant-based ‘fish‘ finally cracking the batter test.

For now, the crown belongs to chicken. It didn’t win the war because it tasted better, but because it adapted faster; to globalisation, culture, and the way Britain eats today. Fish once fed a nation. Chicken learned how to entertain it.